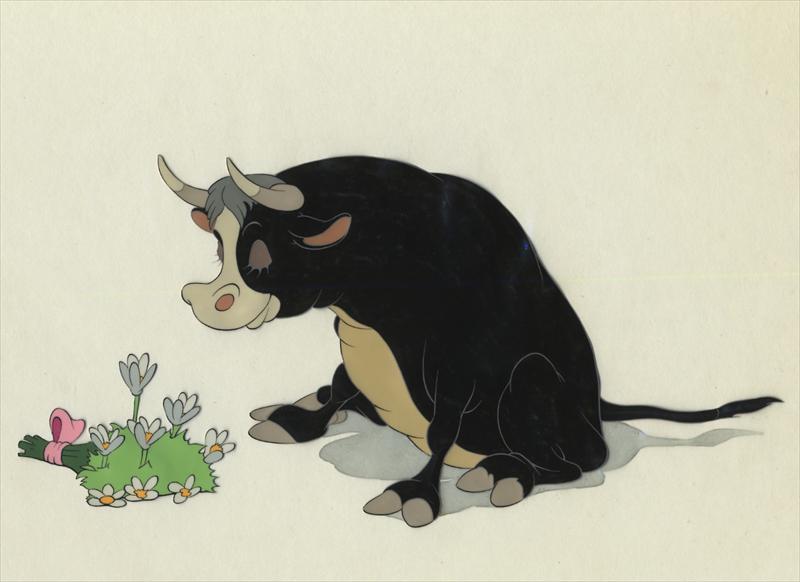

The Story of Ferdinand (1936) is a much acclaimed classic children book written by American author Munro Leaf and illustrated by Robert Lawson. This post reveals the fragrant (and so far ignored) message of the plot.

Smell Culture revisiting classic stories

Some readers might wonder about the broader context of our series Ferdinand&. Why do we care about this story? Why is it important to reveal the fragrant message of this story? Why do we revisit a classic story? Shouldn’t we rather cover the latest release of a fancy niche label? Or promote some interesting olfactory art project?

Subscribers to our website know that we are not under some sort of obligation to applaud every inanity that presents itself as scent communication, a fancy gadget, a brand or even as olfactory art. Scent Culture Institute is not a cheerleader!

Moreover, readers might remember some older posts that revisited classic stories and took a scent-culture perspective: A while ago, we revisited the story of the entombment of Christ and the visual representation of the olfactory intimacy between Mary Magdalene and Jesus’ body. In a similar vein, we also looked at the story of the old and blind Issac blessing his son Jacob and identified the story as a scent masquerade.

Thus, our series Ferdinand& and our interest in The Story of Ferdinand is part of a bigger picture. In fact, we believe it is an important task of scent or smell culture studies to revisit classic narratives and look for the role of the hidden sense of smell. And if there is a fragrant or a smelly message we consider it worth sharing because it distorts and rewrites the traditional order of the senses. Admittedly, our selection might be idiosyncratic. This is one reason why a fragrant key message as revealed and presented here makes a difference. But there is more than a “fragrant message”.

Revealing the agency of the sense of smell

One usually thinks of the sense of smell as a contextual factor. Accordingly, smell is merely an environmental aspect, passive and hardly making any big difference. Along these lines the sense of smell is regarded as entirely lacking any particular agency.

However, our sniffing through the stories reveals a different role of olfactory phenomena. In fact, we argue in favor of the agency of the sense of smell in the story of Ferdinand.

Sensory ethnographer Sarah Pink describes an event as an “ecology of social, material, affective and sensory environmental processes”. Accordingly, things in movement combine to constitute place and the perception of place. Interestingly, Sarah Pink also examines bullfights:

“The bullfight as place-event is each time reconstituted through the convergence of an intensity of things in process, emotions, sensations, persons and narratives. They are sufficiently similar to previous bullfights to be recognizable as the same event, but they actually constitute a new place-event. The performance of the bullfight is thus much more than embodied. It is better interpreted as part of a complex ecology of things.”

Consequently, sensory ethnographers look for examples of specifically sensed experience and consider the constraints of written and spoken language. Our reading of the story of Ferdinand as a sensory narrative reveals that sensory studies do not only face the constraints of written language. No doubt. It is certainly a challenge to capture experiences that precede interpretation, communication or even active awareness. Yet, prior to this there is also the task to even notice the relevance of the senses in a written text.

More than scratch & sniff

In 2015, the Museum of the Moving Image hosted an exhibition on the future of storytelling including a children’s book that could shoot delicious scents directly into the reader’s face. In fact, Goldilocks and the Three Bears: The Smelly Version was presented as “just the first in a series of children’s classics”. Three years later, we have not heard anything about number two or number three of the children’s classics. On the contrary the first in series of children’s classics is not even available on Amazon.

Why is this important when reflecting on The Story of Ferdinand and its implications for scent or smell culture?

The Story of Ferdinand shows that you telling sensory stories does not require an exposure to scents. Moreover, the value proposition of some sophisticated scratch & sniff is not as clear as some enthusiasm about technology might suggest. Instead, one can learn a lot about smelling without even smelling.

Inviting criticism and other possible cases

Obviously our interpretation is open to criticism. And we are eager to learn about your reading and watching. Moreover, we are also interested to hear about other narratives that might be a worth and promising theme for an upcoming new edition of Scent Culture Comment & Review.

Ferdinand &

This post completes our short series Ferdinand&. Subscribing to our updates you will not miss upcoming news, comments and inghts!

[blog_subscription_form title=”” title_following=”You are already subscribed” subscribe_text=”” subscribe_logged_in=”Click to subscribe to this site” subscribe_button=”Click me!” show_subscribers_total=true]

References:

Pink, S. (2011). From embodiment to emplacement: Re-thinking competing bodies, senses and spatialities. Sport, Education & Society, 16(3), 345–355.

Image source:Â http://auction.howardlowery.com/Bidding.taf?_function=detail&Auction_uid1=3080924