The Story of Ferdinand also has a remarkable cinematic history: This post revisits the short animated film adapted by Walt Disney 1938 and reveals its craftmanship in showing olfactory practices.

Category Archives: Scent Culture Comment & Review

comments and reviews: SCI shares views, observations – there should be a SCI contribution

Ferdinand & the pleasures of olfactory perception (1)

The Story of Ferdinand is a much acclaimed classic children book written by American author Munro Leaf and illustrated by Robert Lawson. This post reveals the fragrant (and so far widely ignored) message of the plot. It is the first chapter in a new series Ferdinand& of Scent Culture Comment & Review.

Continue reading Ferdinand & the pleasures of olfactory perception (1)

More than functional bottles: Scent & Symbolism

A recent exhibition on perfumed objects and images provides the context for a few remarks on the role of flacons. Even after the finassage the catalogue deserves more attention. Continue reading More than functional bottles: Scent & Symbolism

Risky media buzz about scent

Marketing experts tell us that negative headlines get much more attention: Continue reading Risky media buzz about scent

“The Art of Scent” 3.0 at Dubai

“The Art of Scent” curated by Chandler Burr at the Museum of Art & Design in New York in 2012 has been a major milestone in the recent history of scent culture. In an interview during the exhibition with Artforum Chandler Burr referred even to perfume (!) “as an artistic medium”. The show presented twelve pivotal fragrances, dating from 1889 to the present. In 2015, it was also presented in Madrid. Later on the show was also presented in Spain.

Given the commercial nature of the scents presented in the exhibition it is almost logical to position the 3rd edition in a shopping mall in Dubai.

Running until July 12, The Art of Scent Exhibition is organised by Perfumery & Co and curated by former New York Times Perfume Critic, Chandler Burr, in collaboration with Art Emaar. The Art of Scent Exhibition delves into the works of Thierry Wasser, Christophe Laudamiel, Patricia de Nicolaï, Daphnée Bugey and Jérome Epinette. According to media coverage Burr has paired each work of scent art with a stylistically and technical similar work of visual art, chosen from s extensive collection of contemporary works – displayed in Fashion Avenue.

[blog_subscription_form title=”” title_following=”You are already subscribed” subscribe_text=”” subscribe_logged_in=”Click to subscribe to this site” subscribe_button=”Click me!” show_subscribers_total=true]

Smelling digital culture

Digital culture seems to epitomize a scentfree world. Information technologies are clean. The sense of smell seems to be the outsider of a digital world. Isn’t this part of the story we tell about progress and a postindustrial society?

Body odor impacting on other’s work performance

Human body odors can transfer anxiety-related signals. This is a well documented fact. Yet, it is an open question how these signals impact in real-life situations. Continue reading Body odor impacting on other’s work performance

ArtBasel 2018: Wake up and smell the…

Art Basel offers a premier platform for renowned artists and galleries. The 49th edition brings together about 290 galleries from 35 countries and opened earlier this week. In fact, “art is now absolutely a consumer product, and that’s the huge difference. It’s a whole different world”, as Paula Cooper recently noted in the New York Times.  Paula Cooper, 80, whose gallery, opened in New York in 1968 has been pivotal in shaping the art world as we know it today. Yet, Art Basel is more than just a fair in the commercial sense of the word. Surprisingly, an attentive visitor can also encounter art in a multi-sensory way and make a few observations on the state of the sense of smell in contemporary art.

Irritating sensation at Art Basel

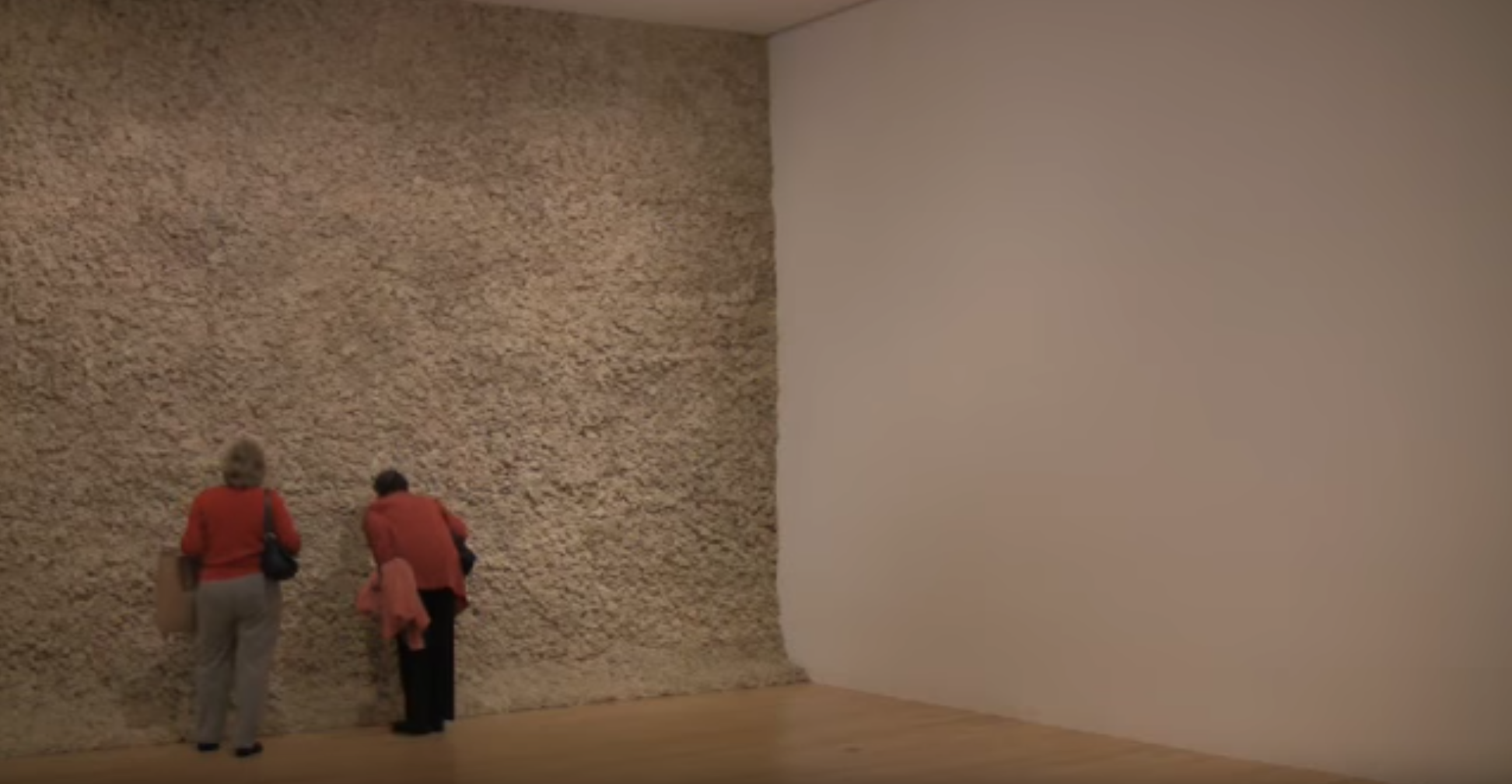

A pungent smell surrounds the booth of the well known Berlin based gallery Neugerriemenschneider. It emanates from Olafur Eliasson’s Moss Wall (1994). And please note: As iterated on the artist’s website the residual scent is an intentional component of the work. Thus, it is not an accidental aspect. The Icelandic-Danish artist was 27 years old and just starting to gain recognition in the international art world when working on the 3.5× 10m sized wall. What one sees and smells is Cladonia rangiferina, which is also called reindeer moss, a lichen native to the northern regions. The lichen is woven into a wire mesh and mounted on the wall of the booth as Eliasson points out on his website. Thus, the work brings a natural phenomena into the highly constructed space of an exhibition, where the visitor might notice how nature might be a construction as well. As the lichen dries, it shrinks and fades. However, when the installation is watered, the lichen expands and emits a pungent odor. The gallerist actually told me about spraying water on the lichen.

Moss Wall as major early work

This major work from Eliasson’s early career has previously been shown at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, SFMOMA in San Francisco, and the Moderna Museet in Stockholm, among other institutions. In 2017, the wall was also part of a group show at GalerÃa Elvira González in Madrid entitled “Sense of Smell”.

The hallways at Art Basel are crowded and packed even during the private days. Since an art fair epitomizes the principles of our attention economy, numerous artworks are in severe competition for the limited attention of the visitors. Thus, it is a special situation for presenting a piece that works with the subtle sense of smell. Yet, I have seen collectors that notice the sharp or irritating sensation of the smelly wall. But the situation differs significantly from the sensory and even meditative experience of a presentation in a museum:

This film published by the Leeum Museum, Seoul captures the sensual experience of the wall:

However, in the specific context of a fair the smell becomes a minor issue. Even people who spend some time at the booth hardly engage with the work in a multi-sensory way as the video from the museum exhibition demonstrates.

Commercial context sanitizes works of art

The commercial context seems to sanitize a work of art that actively involves the sense of smell. Talking to the gallerist I got the impression that for him the sensory qualities of the work are of minor importance. Yet, it is pretty clear that the smell is conceptually a key element for showing “constructed nature”.

Smell & attention economy

Let’s come back to the attention economy. The pungent moss smell does certainly not evoke the pleasant ambience of a luxury retail setting. Yet, the moss smell might be an important factor in the attention economy. The booth subtly attracts attention across different sensory modalities. Thus, it might not be a surprise that the online platform Artsy, some call it the “Pandora for art,†lists the the booth among the 15 Best Booths at Art Basel and discuses the Moss Wall as one of two works that stand out:

Wake up and smell the art!

Stay updated and enter your email address to follow us!

[blog_subscription_form title=”” title_following=”You are already subscribed” subscribe_text=”” subscribe_logged_in=”Click to subscribe to this site” subscribe_button=”Click me!” show_subscribers_total=true]

We have actually shared observations from Art Basel before. If you missed this, please have a look.

“The future will be like perfume”

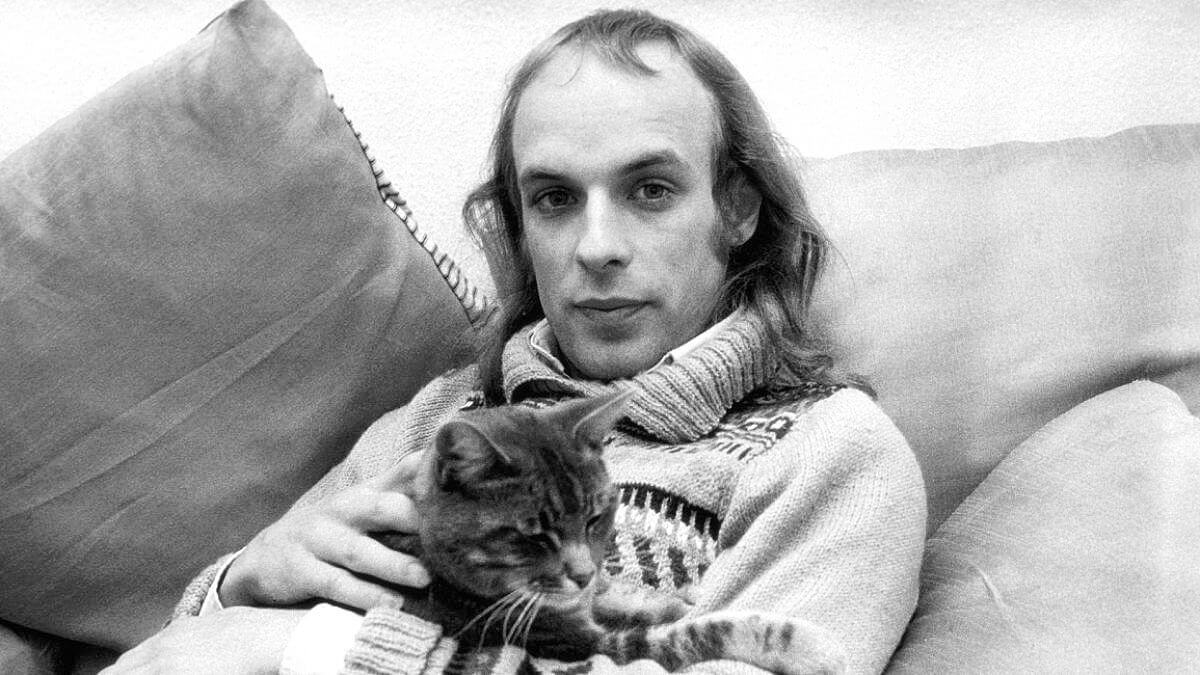

Brian Eno altered the course of both pop and experimental music. He is now 70 years old. After leaving Roxy Music in 1973, he went on to become one of the most widely extolled producers of the late 20th century. He’s also become a legendary solo artist in his own right and has lately found a home on electronic music’s iconic Warp Records. Earlier today, the American biweekly popular culture magazine Rolling Stone provided a short introduction to his oeuvre:

“Eno’s mammoth discography spans half a century of recorded music. Many people know him best as a producer and collaborator – a key force behind stone-cold classics like David Bowie’s Low and Heroes (produced by Tony Visconti and aided mightily by Eno), Talking Heads’ Fear of Music, Devo’s debut album Are We Not Men? We Are Devo!, U2’s The Joshua Tree and dozens upon dozens more. In the early Seventies, when Eno was in his early twenties, he was Roxy Music’s synthesist and sonic magician, leaving an unforgettable mark in his brief three years in the band before releasing four offbeat and hugely influential rock albums of his own, and collaborating with King Crimson’s Robert Fripp and the German group Cluster, among others. In between all of this, he put forth the modern concept of ambient music. Scores of albums and collaborations followed – encompassing the histories of rock & roll, electronic music, experimental music, soundtrack music and seemingly everything else.”

A few weeks ago the Guardian noticed en passant that Eno never stopped making interesting ambient records and discussed a recent CD set as the contemporary album of the month.

Neroli

In 1993 Eno released an ambient instrumental album called Neroli, named after the syrupy sweet, floral and heady essential oil produced from the blossom of the bitter orange tree. A click on the cover takes you to the piece on youtube:

Conceived as a single piece, Eno describes it in the liner notes as “to reward attention, but not so strict as to demand it”. Single notes resonate throughout the piece in a seemingly random but harmonic pattern that shifts quietly for close to an hour. Thanks to the calming nature of the piece,

Neroli has been implemented in some maternity wards, both to instill a sense of calm as well as enhance the organic nature of childbirth. According to the notes accompanying the CD, Eno intended to release a longer version for just that purpose.

The future will be like perfume

In 1992 Brian Eno explained some of the roots of his musical interpretation in an essay entitled:Â Â The Future Will Be Like Perfume:

Interestingly, Eno also grapples with the inconsistencies and challenges of classifying smells:

â€Like others who’ve played with perfumes, I found this somewhat unsatisfactory. I wanted a system, a map. I briefly thought I might be able to make one myself, but this plan foundered as I jotted down the resemblance between strawberries and egg yolk, between breweries and certain types of horsehair bedding.â€

Though he does not refer to the smelly wheels. But there is reason to believe that he considered them to be unsatisfactory.

What is really worth reading about Brian Eno’s essay is how he connects the undercurrents of our time to perfumery. He uses the experience of scent to interpret key themes of age:

We find ourselves having to frequently reassess or even reconstruct them completely. We are, in short, increasingly uncentered, unmoored, lost, living day to day, engaged in and ongoing attempt to cobble together a credible, at least workable, set of values, ready to shed it and work out another when the situation demands. (…) Perhaps our sense of this, the sense of belonging to a world held together by networks of ephemeral confidences (such as philosophies and stock markets) rather than permanent certainties, predisposes us to embrace the pleasures of our most primitive and unlangued sense.

Isn’t it remarkable how one connect a clear Zeitdiagnose to a sensory experience?

[blog_subscription_form title=”” title_following=”You are already subscribed” subscribe_text=”” subscribe_logged_in=”Click to subscribe to this site” subscribe_button=”Click me!” show_subscribers_total=true]

Sources: The featured image is a screenshot from Brian Eno – Thursday Afternoon.

“Scent Culturalizing” the end of an industrial era

Germany will shut down its remaining black coal mines by the end of this year. This plan seals the fate of the sector that powered the country’s industrial revolution and post-war economic miracle. Since its early beginnings in the early 1970s this fundamental shift has had widespread implications the former industrial heartland of Germany. Given its links to human memory smells are medium of choice to work on the end of an industrial age.

Thus, the Art Museum at Mühlheim an der Ruhr takes this opportunity to invite Helga Griffiths, an artist who has been working across the boundaries of science, technology and different media (including the sense of smell) for quite a while. We have previously wrote about her work.

For the upcoming exhibition (6 May – 16 September 2018) Griffiths starts with coal as a material for different transformative processes. Destillation technologies are used to arrive at the essence of coal. A special scent edition will be offered on the occasion of this exhibition (allowing the user to keep memories of this passing industrial age).